FALL 2017 / 17

In 1950, Robert Lerer was a boy of

Eastern European heritage playing with

his friends in Havana, Cuba. His parents

had moved there after eeing Poland for

France during World War II. His parents

never talked about the war. Their lives

before his birth in 1946 were a mystery

to him, although he knew that many of

his Jewish family members had died in

the Holocaust.

In 1953, Lerer was a boy of 7 years

old, being raised in the Catholic Church

on a northern Caribbean island where

a revolution was just beginning—a

revolution that would last for ve years,

ve months, and six days.

In November of 1960, Lerer was a boy

of 14, whose parents told him that they

were taking him and his brother away

from Cuba to a city in America: Miami.

They were part of a historic wave of more

than 100,000 refugees who emigrated

from Cuba to countries around the world

after Castro-led revolutionaries overthrew

the Fulgencio Batista regime in 1959.

In the summer of 1961, Lerer’s family

moved to Birmingham, where his father,

Joseph Lerer, had been admitted to

the University of Alabama School of

Dentistry. Both of Robert’s parents were

already dentists before leaving Europe; his

father had been an oral surgeon in Cuba,

and his mother was a teacher in Cuba.

Robert attended Ramsay High School.

As he applied to colleges throughout

Alabama, he thought maybe one day he

could be an engineer.

These were the moments in history that

marked Lerer’s path to BSC in 1962. It was

at BSC that his path changed course.

“A chemistry professor, Wynelle

Thompson, changed my life,” he said.

“She saw that I was more suited for

something else.”

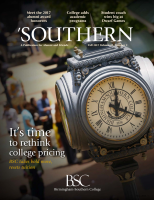

In 2017, Lerer is an esteemed

physician with a long career of service,

decades spent in service to the place he

lives and the place from which he came.

He is associate professor emeritus of

pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati

College of Medicine and Cincinnati

Children’s Hospital Medical Center

and is one of the longest serving health

commissioners in the state of Ohio;

he volunteers in underserved areas

around the world; and this fall, he will

be one of the honorees receiving BSC’s

Distinguished Alumni Award.

After graduating

magna cum laude

—

and as valedictorian of his class—with

a bachelor’s in chemistry in 1966, he

attended Johns Hopkins University

Medical School and excelled there.

“I would not have been third in my

class at Johns Hopkins without my

education from BSC,” he said. From

there, he continued his post-graduate

education in pediatrics at Yale University

and became chief resident. He is an expert

in neonatology and has reviewed and

consulted on thousands of newborn cases.

“God gave me skills and intelligence

and drive, but all of that really developed

while I was at college,” Lerer said.

“Birmingham-Southern made all the

difference in my life.”

Long before the phrase “lives of

signi cance” became common on

campus, it was a way of life on the

Hilltop.

“Being a servant to others, being a

person of integrity, and having a purpose

in life was very important,” he added.

“It’s one of the reasons I chose to go into

pediatrics. Pediatricians become advocates

for children.”

A lasting impression

As much as his early years were marked

by revolution, Lerer’s time at BSC also

occurred in the midst of unrest.

“Birmingham was still segregated at that

time, as was BSC,” he said. “It was only

natural that I became friendly with groups

that, at that time, felt like demonstrating

openly our displeasure with the Jim

Crow laws. I remember vividly going

to work after chemistry lab—I worked

at Birmingham Book and Magazine

Company downtown and parked my old

beat-up 1956 DeSoto near Kelly Ingram

Park—and seeing Bull Conner using hoses

and dogs. I witnessed those things with

my own eyes.”

On May 3, 1963, 60 young people

were arrested in the vicinity of the park.

The next day, thousands more arrived to

demonstrate. In April of that year, Martin

Luther King Jr. wrote his “Letter from a

Birmingham Jail.”

Lerer recalls another time when the

segregation of the South was made clear

to him personally.

“Not being from the United States, this

had a very deep impact on me,” he said.

“In Cuba, there were no outward signs

of discrimination; brown children and

black children and white children played

The thing about history is that before it becomes

history, it’s a series of days in someone’s life.

Bottom photo: Lerer with a team of

medical faculty from Christian Medical

& Dental Associations